- Movie producers hold final accountability for financing, scheduling, legal compliance, and delivery; directors control creative execution and audience experience.

- Producer-director conflict occurs when creative choices increase cost, delay schedules, misalign markets, or jeopardize legal, technical, or distribution deliverability.

- Movie producers assume financial risk with deferred or equity-based compensation, while directors receive guaranteed fees and face career risk primarily.

I have worked on projects where the producer and director functioned as a single strategic unit, and I have also worked on productions where that relationship collapsed. In every case, the outcome of the film reflected the clarity or confusion between those two roles.

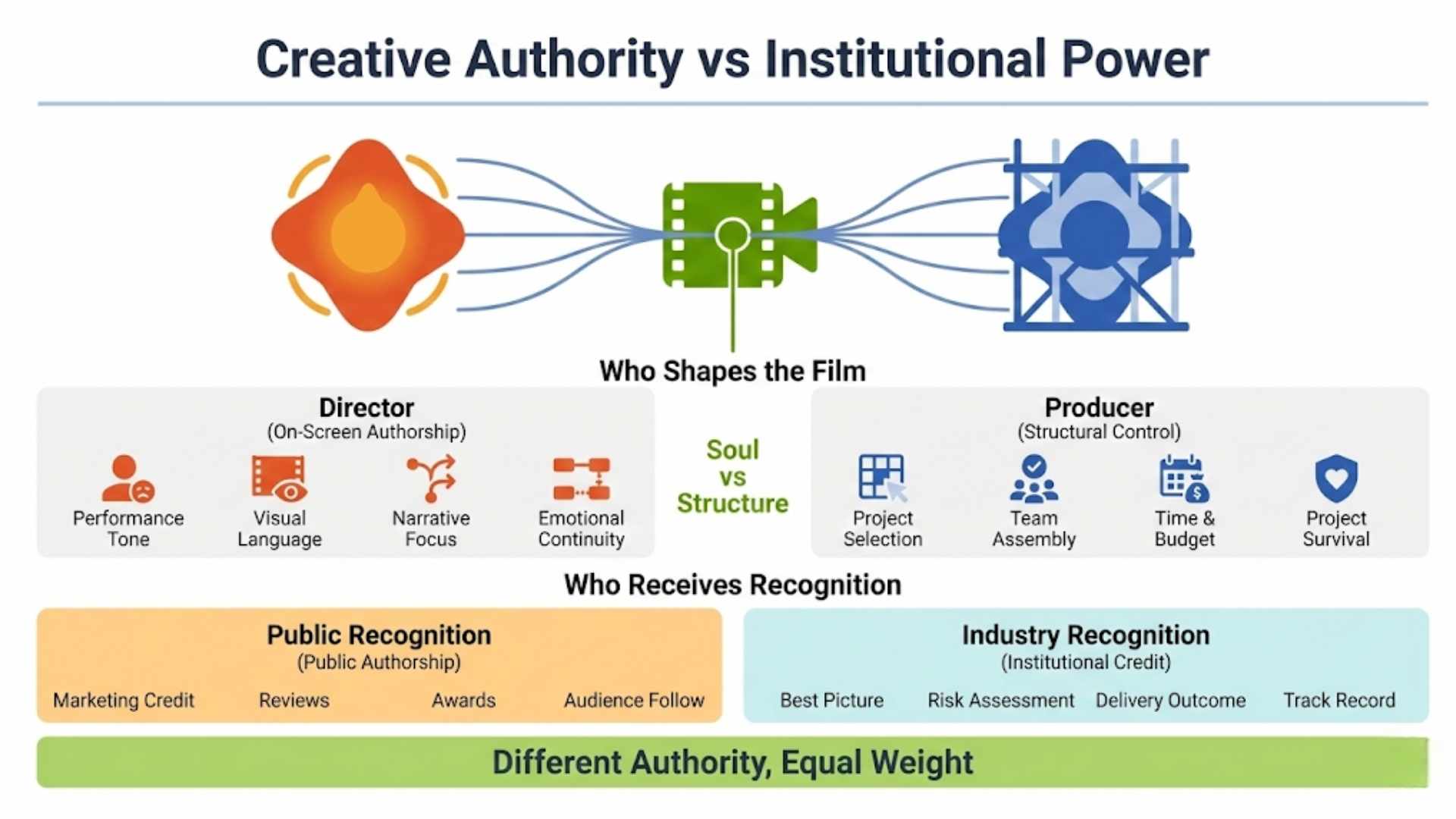

The producer and the director do not compete for authorship. They exercise two different kinds of authority inside the same system. When people treat them as interchangeable or when one role attempts to dominate the other, production integrity breaks down.

This article examines the roles as they actually function in professional filmmaking: structurally, creatively, financially, and operationally. I am not writing for students or hobbyists. I am writing for practitioners who need a precise understanding of where power, responsibility, and authorship truly sit.

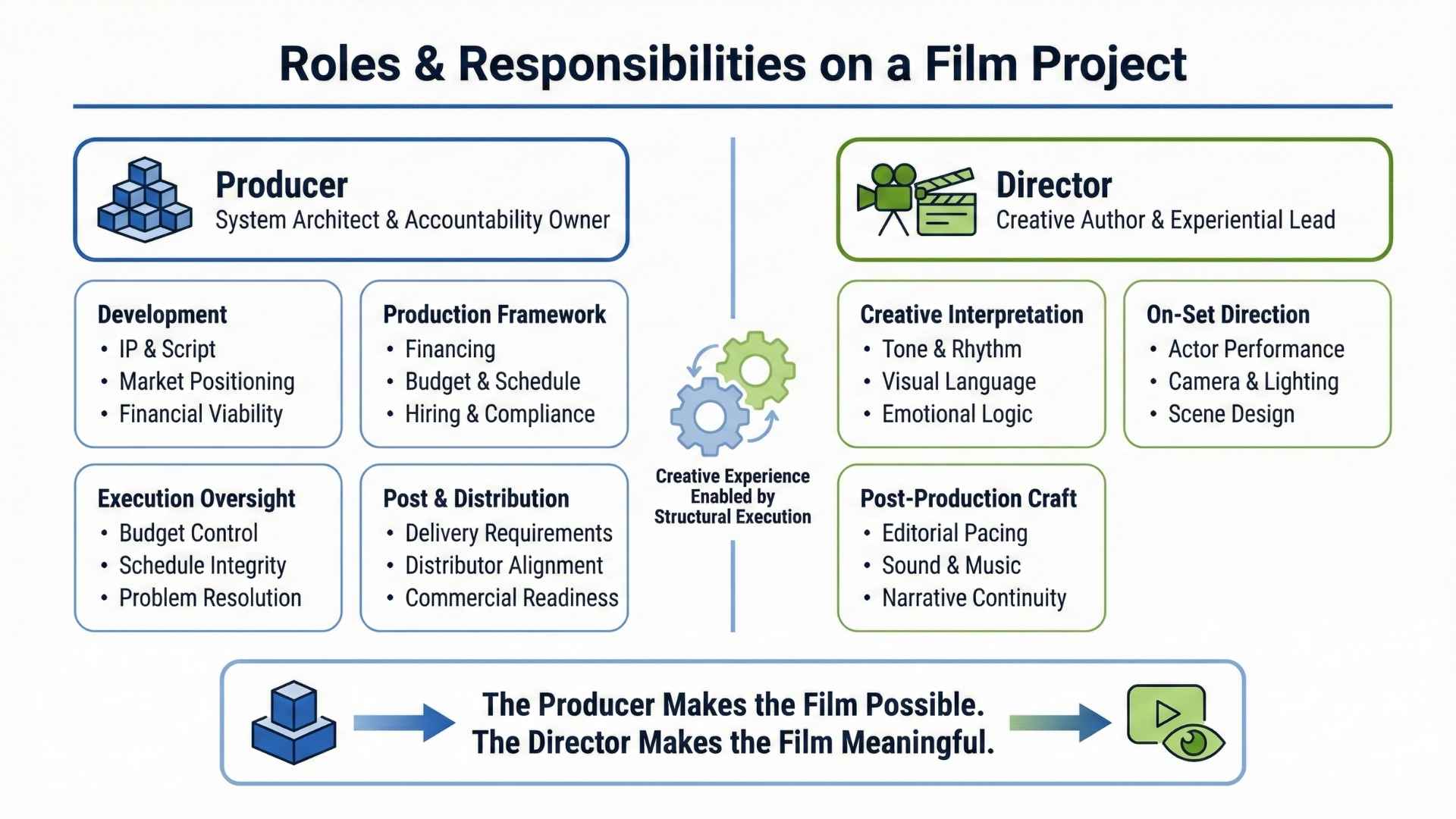

Roles and Responsibilities on a Film Project

Roles and Responsibilities on a Film Project

The Producer’s Role

I approach producing as a form of structural authorship. The role is not simply about managing a project. It is about determining whether a film can exist at all, and under what conditions it can survive.

My involvement begins long before the cameras roll. At the earliest stages of development, I typically:

- Develop or acquire the underlying material, whether that is original IP, a script, or adaptation rights.

- Shape the project’s direction through development notes, rewrites, and market positioning.

- Evaluate whether the concept is financially viable within realistic budget parameters.

Once a project moves forward, my focus shifts to building the production framework:

- Securing financing through studios, investors, tax incentives, or co-production structures.

- Setting and approving the budget, including contingency and delivery requirements.

- Hiring the director and department heads and approving principal casting.

- Defining the production schedule and ensuring union, legal, and insurance compliance.

During production, my responsibility centers on maintaining system integrity:

- Tracking budget burn in real time.

- Monitoring schedule movement and intervening when delays threaten completion.

- Resolving logistical failures, location issues, labor challenges, and contractual conflicts.

In post-production and distribution, the role becomes increasingly strategic:

- Overseeing editorial timelines and test screening strategy.

- Aligning the final cut with distributor requirements, ratings considerations, and marketing plans.

- Ensuring the film is delivered legally, technically, and commercially to buyers and platforms.

Producing is not simply about management. It is about accountability. When a film fails to be completed, delivered, or monetized, that responsibility ultimately sits with the producer.

The Director’s Role

The director is the film’s creative author. Once production begins, the director controls how the story is expressed, interpreted, and emotionally experienced.

I rely on the director to convert the script into a coherent cinematic language. That includes defining:

- Tone, rhythm, and emotional logic.

- Visual grammar, such as framing, movement, composition, and color.

- Performance dynamics and character interpretation.

On set, the director exercises creative command:

- Directing actors to shape performance, subtext, timing, and emotional continuity.

- Working with the cinematographer to determine camera placement, lensing, and lighting.

- Designing scene structure so that each moment advances narrative and emotional objectives.

In post-production, the director refines meaning:

- Collaborating with editors on pacing, structure, and narrative clarity.

- Shaping sound design, music, and transitions to reinforce tone and emotional impact.

- Ensuring visual and dramatic continuity across the entire cut.

Even when I retain final approval authority, the director remains the primary creative architect. The film’s emotional and aesthetic identity belongs to them.

If I define the system that allows the film to exist, the director defines the experience that gives it value.

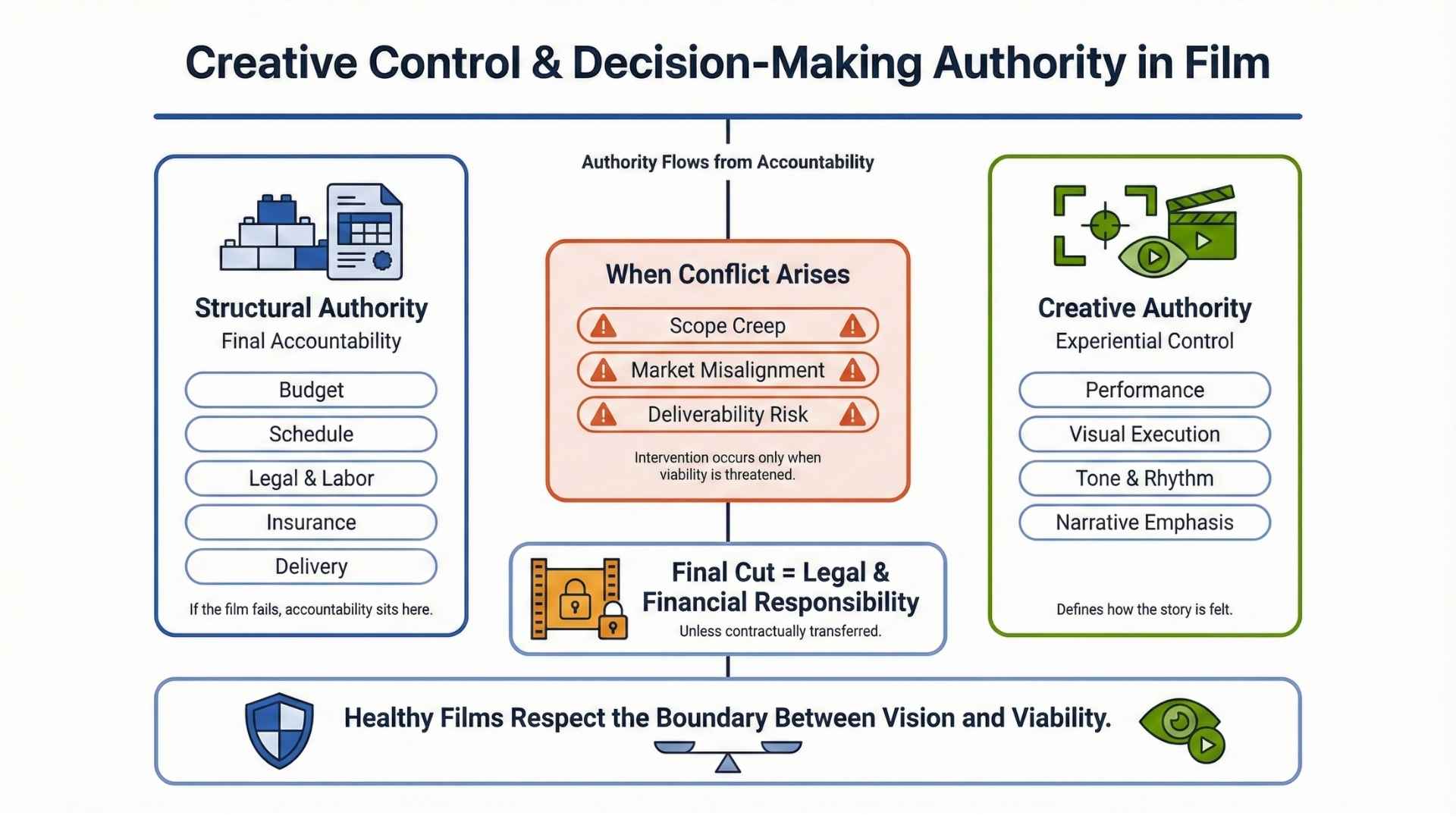

Differences in Creative Control and Decision-Making Authority

Differences in Creative Control and Decision-Making Authority

Authority on a film is layered. It is not divided into “business versus art.” It is divided by accountability.

Structural Authority

As producer, I carry final responsibility for:

- Budget adherence.

- Schedule integrity.

- Legal, labor, and insurance compliance.

- Delivery to financiers, distributors, and completion guarantors.

If the project collapses, exceeds budget, or violates contractual terms, that accountability flows to me. This is why the producer hires the director and not the other way around.

Creative Authority

On set and in post, the director holds creative command:

- Performance direction.

- Visual execution.

- Narrative emphasis and emotional pacing.

I do not direct the film. I do not dictate camera movement, performance nuance, or scene rhythm. When I intervene creatively, it is not aesthetic. It is structural.

When Conflict Arises

Disagreements typically fall into three categories:

- Scope: A creative choice expands cost or schedule beyond what the project can sustain.

- Market alignment: A creative direction undermines audience positioning or distribution commitments.

- Deliverability: A creative decision creates legal, ratings, or technical obstacles to release.

In those situations, I intervene because I remain accountable for completion and exploitation of the film.

Final Cut

Unless a director contractually negotiates the final cut, editorial authority ultimately resides with the producer or studio. This is not philosophical. It reflects where legal and financial responsibility sits.

Healthy collaborations depend on trust:

- I protect the director’s vision wherever possible.

- The director respects the operational boundaries that keep the film viable.

When either side disregards the other’s domain, the work suffers.

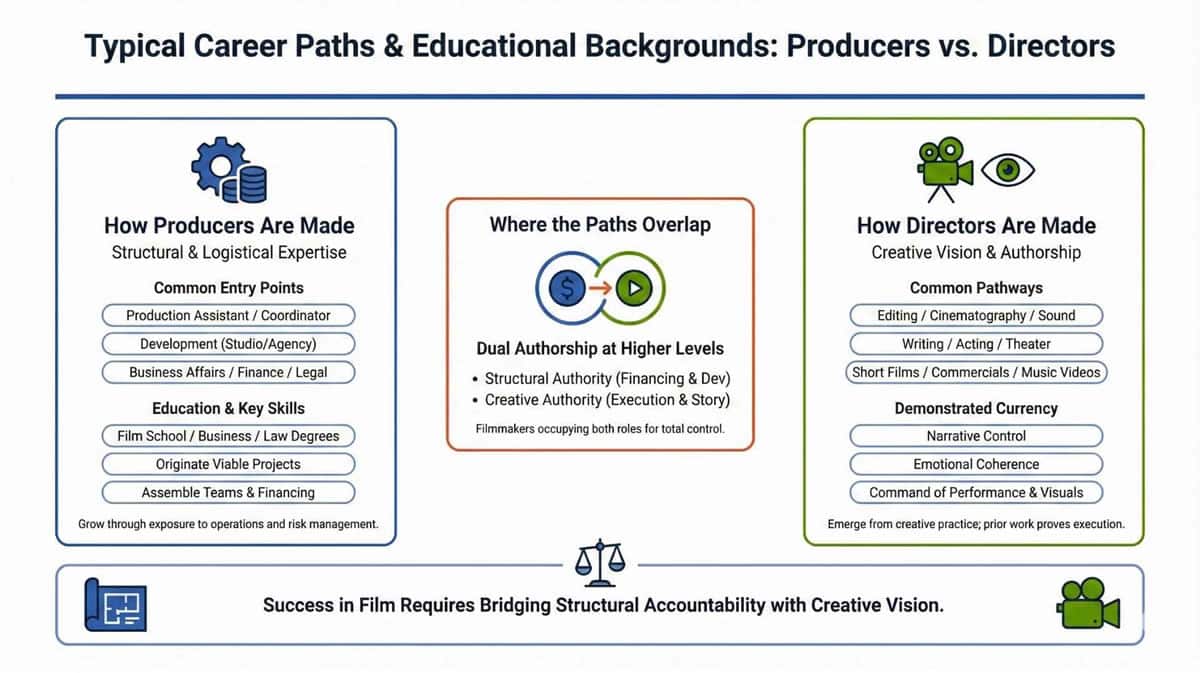

Typical Career Paths and Educational Backgrounds

How Producers Are Made

Most producers do not enter the industry as producers. They grow into the role through exposure to development, finance, and production operations.

Common entry points include:

- Production assistant and coordinator roles that build logistical and scheduling expertise.

- Development positions at studios, agencies, and production companies.

- Business affairs, finance, or legal backgrounds that provide fluency in contracts, rights, and deal structures.

Education varies widely. Film school, business degrees, and law degrees all produce capable producers. What ultimately matters is the ability to:

- Originate viable projects.

- Assemble teams and financing.

- Manage risk across multi-year timelines.

How Directors Are Made

Directors typically emerge from creative practice. Their authority is built on demonstrated authorship.

Common pathways include:

- Editing, cinematography, production design, or sound.

- Writing, acting, or theater.

- Short films, commercials, music videos, and independent features.

A director’s currency is vision. Studios and producers hire directors based on what their prior work proves they can execute.

Formal training can refine craft, but it cannot substitute for a body of work that demonstrates:

- Narrative control.

- Emotional coherence.

- Command of performance and visual language.

Where the Paths Overlap

At higher levels of the industry, many filmmakers occupy both roles. They produce in order to direct their own work or direct in order to retain control over projects they originate.

This dual authorship allows them to command both:

- Structural authority over financing and development.

- Creative authority over execution and storytelling.

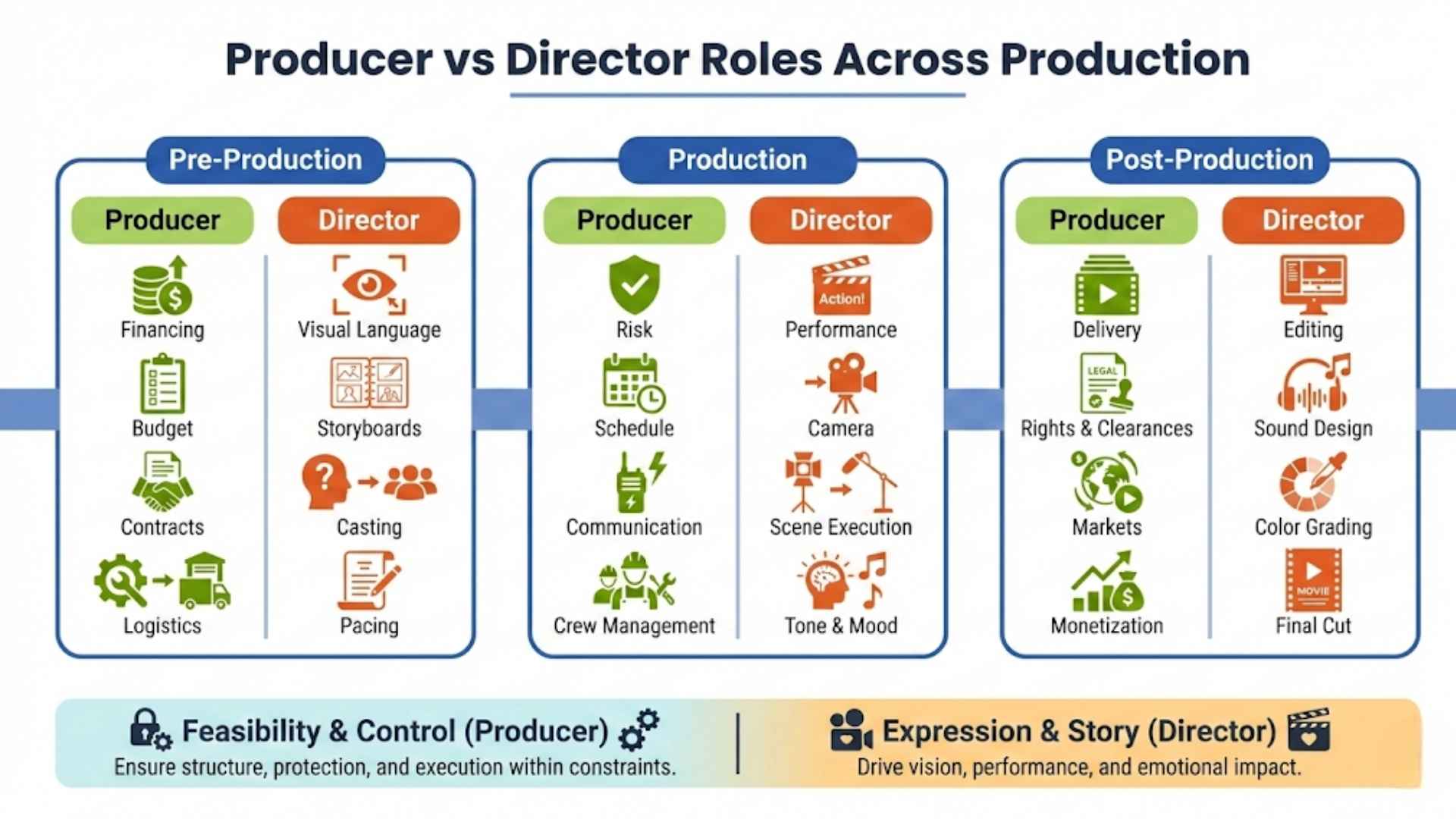

Day-to-Day Tasks Across Production Phases

Day-to-Day Tasks Across Production Phases

Pre-Production

As a producer, I construct the operational framework:

- Finalizing financing structures and closing capital.

- Locking budgets and contingency.

- Hiring department heads and negotiating contracts.

- Clearing rights, insurance, and union requirements.

At the same time, the director constructs the creative framework:

- Developing the visual language of the film.

- Storyboarding and designing shot logic.

- Casting and conducting rehearsals.

- Collaborating with production design, costume, and cinematography.

We meet continuously. I shape feasibility. The director shapes expressions.

Production

On set, responsibilities diverge clearly.

I focus on:

- Schedule compliance.

- Budget management.

- Labor and safety.

- Delivery benchmarks.

The director focuses on:

- Performance direction.

- Scene execution.

- Camera strategy and visual continuity.

- Creative problem-solving in real time.

If a sequence exceeds schedule, I restructure the plan. If weather or logistics collapse a location, I replace it. If a creative approach becomes impractical, I negotiate alternatives. The director never has to manage insurance, penalties, or contractual exposure. That remains my responsibility.

Post-Production

Post becomes strategic rather than operational.

I oversee:

- Editorial schedules and cost controls.

- Test screenings and market response.

- Distributor and platform requirements.

The director refines:

- Narrative structure and pacing.

- Sound, music, and tonal cohesion.

- Emotional clarity and story resolution.

If revisions are required for legal, commercial, or technical reasons, I manage that process while preserving creative intent wherever possible.

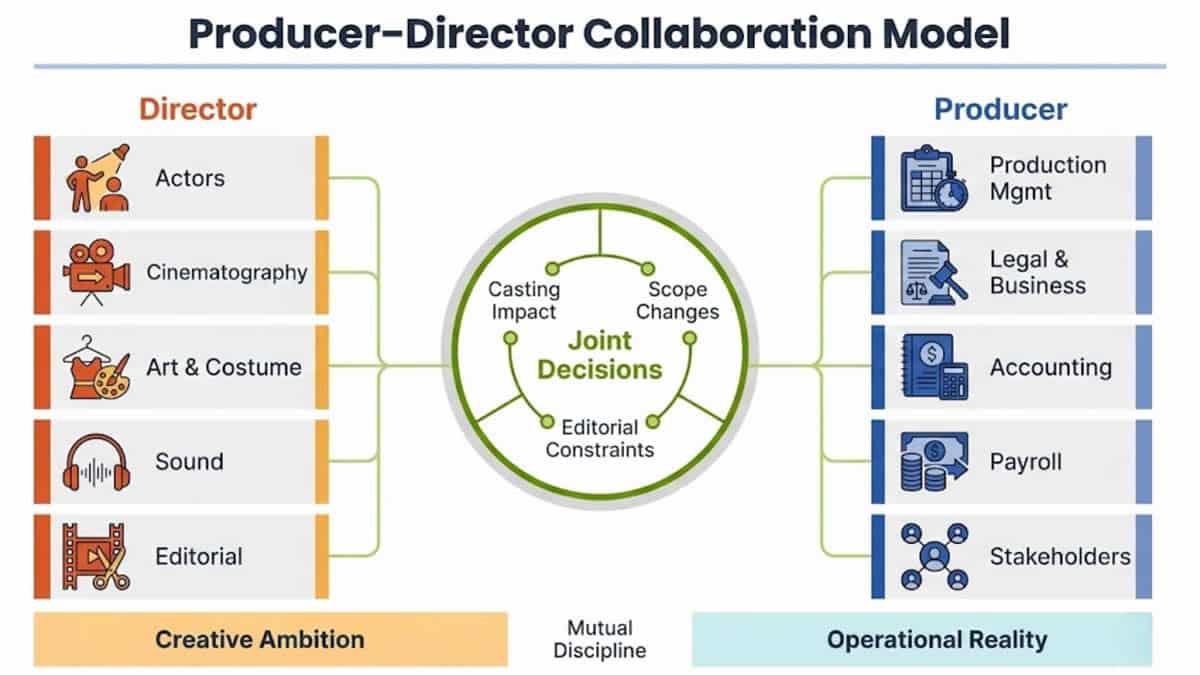

How Producers and Directors Collaborate With Each Other and With the Cast and Crew

A professional production succeeds when authority flows through clearly defined channels.

The director leads the creative workforce:

- Actors.

- Cinematography.

- Art, costume, sound, and editorial.

I lead the production infrastructure:

- Production management.

- Legal and business affairs.

- Accounting and payroll.

- External stakeholders including financiers and distributors.

We converge on decisions that affect both domains:

- Casting that impacts budget or marketability.

- Script or structure changes that alter scope.

- Editorial choices tied to ratings, runtime, or delivery requirements.

When the relationship is disciplined and mutual, creative ambition and logistical reality reinforce each other. When it becomes adversarial, the film fragments.

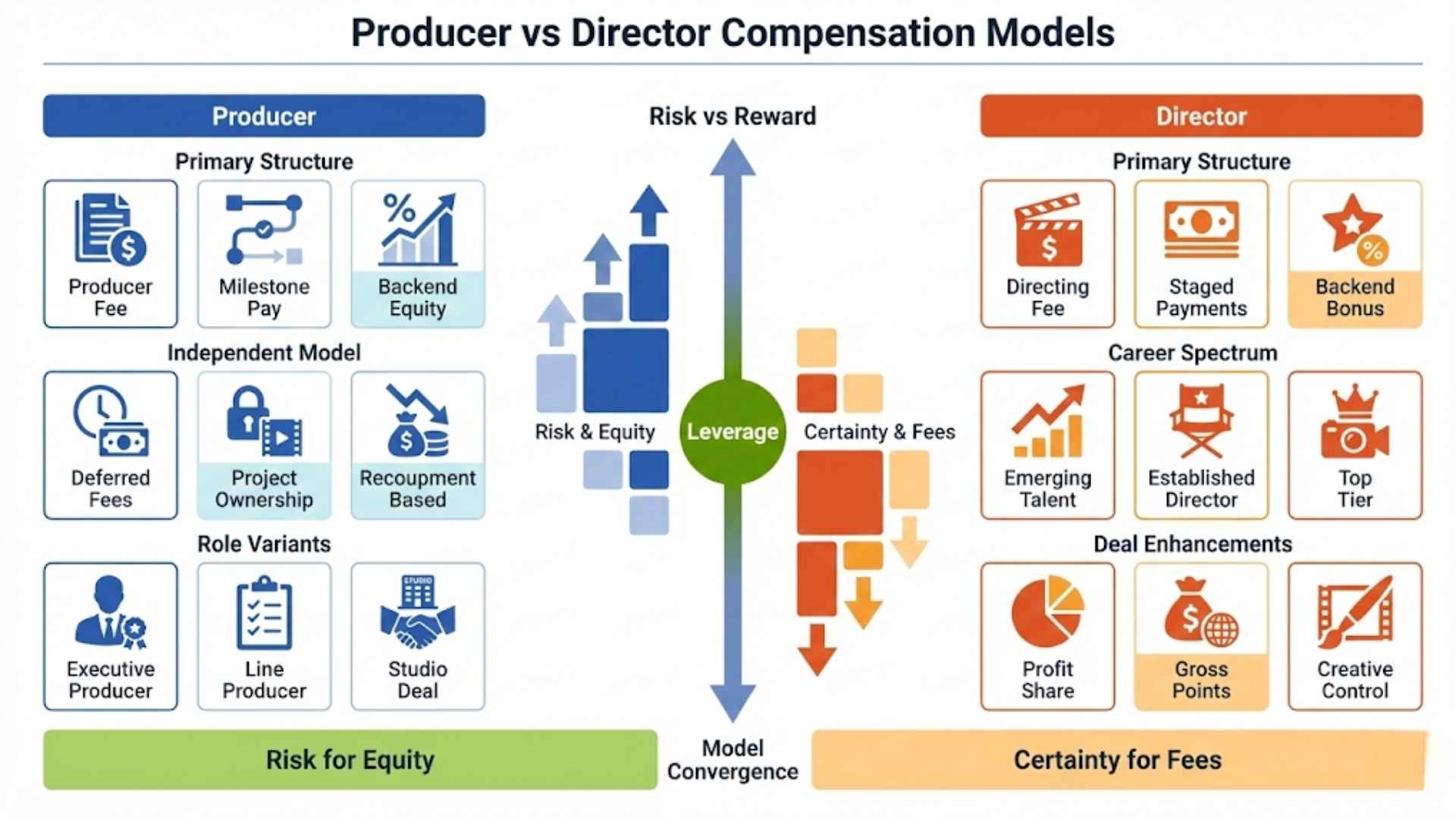

Salary Ranges and Compensation Structures

Salary Ranges and Compensation Structures

Compensation in this industry reflects leverage, risk exposure, and market value rather than job title alone. Producers and directors can both earn very little or extraordinary sums depending on where they operate in the ecosystem and how much authority they carry over the project.

How Producers Are Paid

As a producer, my income is rarely a simple paycheck. It is usually a layered structure tied to development, production, and performance.

On studio and well-financed projects, compensation typically includes:

- A producer fee linked to the overall budget.

- Payment milestones tied to development, principal photography, and delivery.

- Performance bonuses or profit participation if the film exceeds benchmarks.

On independent productions, the structure is often risk-heavy:

- Fees are frequently deferred until financing closes or distribution is secured.

- Ownership in the project replaces or supplements upfront payment.

- Compensation depends on recoupment and long-term performance rather than immediate cash flow.

This is where producing becomes entrepreneurial. I may spend years developing a project with no guarantee of compensation. I often absorb costs personally in order to keep a project alive. When a film performs well, the upside can be significant. When it fails or never reaches production, the loss is mine.

Different producer titles also carry different compensation models:

- Executive producers often receive flat fees or backend participation tied to financing, packaging, or distribution.

- Line producers and unit production managers are usually paid salaries per project based on schedule length and budget scale.

- Institutional producers working under studio or platform deals may receive annual overhead plus performance incentives.

At the highest tier, producers operate under multi-year agreements with studios or platforms. These include first-look arrangements, guaranteed development funding, and long-term overhead. At that level, producing becomes institutional rather than transactional.

How Directors Are Paid

Directors are usually compensated through a fixed directing fee. That fee scales according to experience, reputation, and the size of the production.

Common structures include:

- A negotiated upfront fee for the directing services.

- Staged payments tied to production milestones.

- Backend participation in profits or revenue on higher-profile projects.

For emerging directors, compensation is often minimal and sometimes symbolic. Many early-career directors accept reduced fees in exchange for visibility, creative opportunity, or long-term leverage.

Established directors command substantial fees. On major studio productions, directing fees can reach seven figures. High-profile directors frequently negotiate:

- Profit participation after recoupment.

- In rare cases, a percentage of gross revenue rather than net profit.

Unlike producers, directors rarely assume direct financial risk. Their contracts generally guarantee payment once production begins, regardless of commercial outcome.

Structural Differences in Risk and Reward

The economic logic of the two roles differs fundamentally.

For producers:

- Income is often tied to ownership and long-term performance.

- Financial risk is real and frequently personal.

- Development work may go unpaid if a project collapses.

For directors:

- Compensation is typically guaranteed once production starts.

- Career risk outweighs financial risk.

- Long-term earning potential depends on reputation and critical or commercial success.

In practice, this means:

- Producers trade stability for equity.

- Directors trade equity for certainty.

At the highest level, these models converge. Director-producers negotiate both fees and ownership. They retain creative control and participate in long-term revenue streams. This is where real leverage exists.

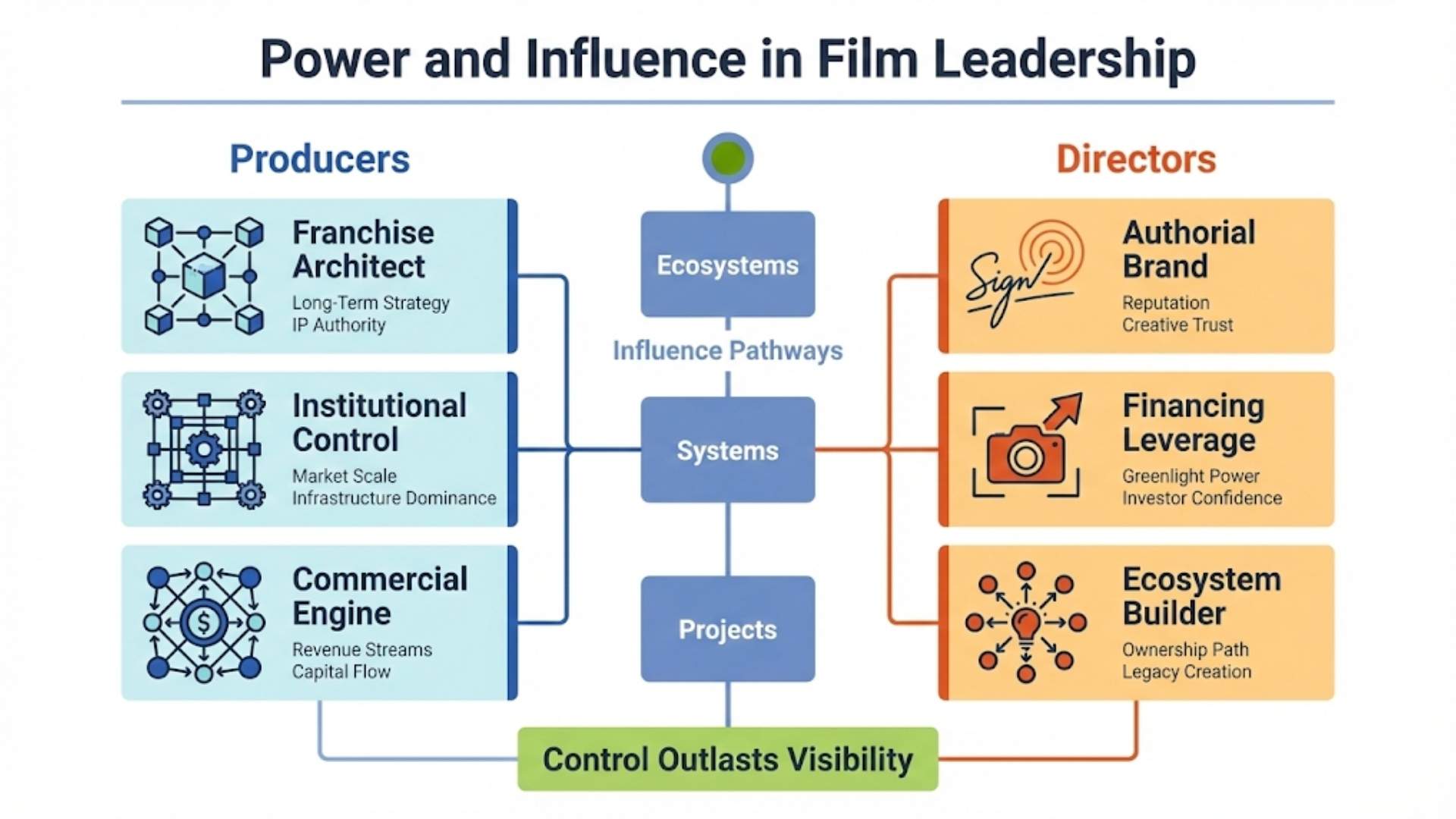

High-Profile Examples of Successful Producers and Directors

High-Profile Examples of Successful Producers and Directors

Producers

Inside the industry, we evaluate power by structural control rather than public visibility.

Kevin Feige functions as a franchise architect rather than a project-specific producer. He defines long-term narrative strategy, hires directors, oversees development, and maintains continuity across an interconnected universe. His authority is systemic rather than film-by-film.

Kathleen Kennedy represents institutional production. As head of Lucasfilm, she controls some of the most valuable IP in the industry. She approves creative direction, oversees development, and makes final personnel decisions. When a production course-corrects or replaces a director, that authority flows through her office.

Jerry Bruckheimer exemplifies the commercial producer. His name signals a specific market identity. Directors rotate in and out of his projects, but the producing infrastructure ensures consistent scale, tone, and audience reach.

These producers demonstrate a central truth of the profession: long-term influence comes from controlling systems, franchises, and financing pathways, not from individual films.

Directors

Directors exert influence through authorship and reputation.

Figures such as Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, and James Cameron illustrate how a director’s name becomes a financing instrument. Studios back projects because they trust the director’s ability to deliver both creatively and commercially.

What is often overlooked is how these directors expand into producing:

- They form production companies.

- They originate and package projects.

- They retain rights and creative oversight.

They do not remain solely in the director role because creative authority without structural authority is always conditional. Control over development and financing allows them to protect their vision and shape their career trajectories.

In professional terms, they transition from authors of films to architects of production ecosystems.

Influence on the Final Film and Public Recognition

Influence on the Final Film and Public Recognition

Who Actually Shapes the Film

Directors shape what appears on screen. They determine:

- Performance tone and emotional continuity.

- Visual language, pacing, and narrative emphasis.

- The experiential identity of the film.

Producers shape the film indirectly but decisively by controlling:

- Which stories enter development.

- Which directors and cast are hired.

- How much time and money are available.

- Whether a project survives at all.

I have seen exceptional creative concepts die because financing collapsed. I have also seen ordinary scripts become strong films because the right team, budget structure, and production strategy were assembled around them. Those outcomes are the result of producing decisions, not chance.

If the director defines the soul of the film, the producer defines its body and its lifespan.

Public Recognition

Directors receive public authorship. Their names appear in marketing, reviews, awards, and critical discourse. Audiences follow directors.

Producers receive institutional recognition. When a film wins Best Picture, the award goes to the producers. Within the industry, success or failure is attributed to the producing team long before creative analysis begins.

This division is structural:

- The public engages with stories and aesthetics.

- The industry evaluates performance, risk, and delivery.

Neither form of recognition is superior. They represent different forms of responsibility and authorship.

Skills and Traits Required for Each Role

Skills and Traits Required for Each Role

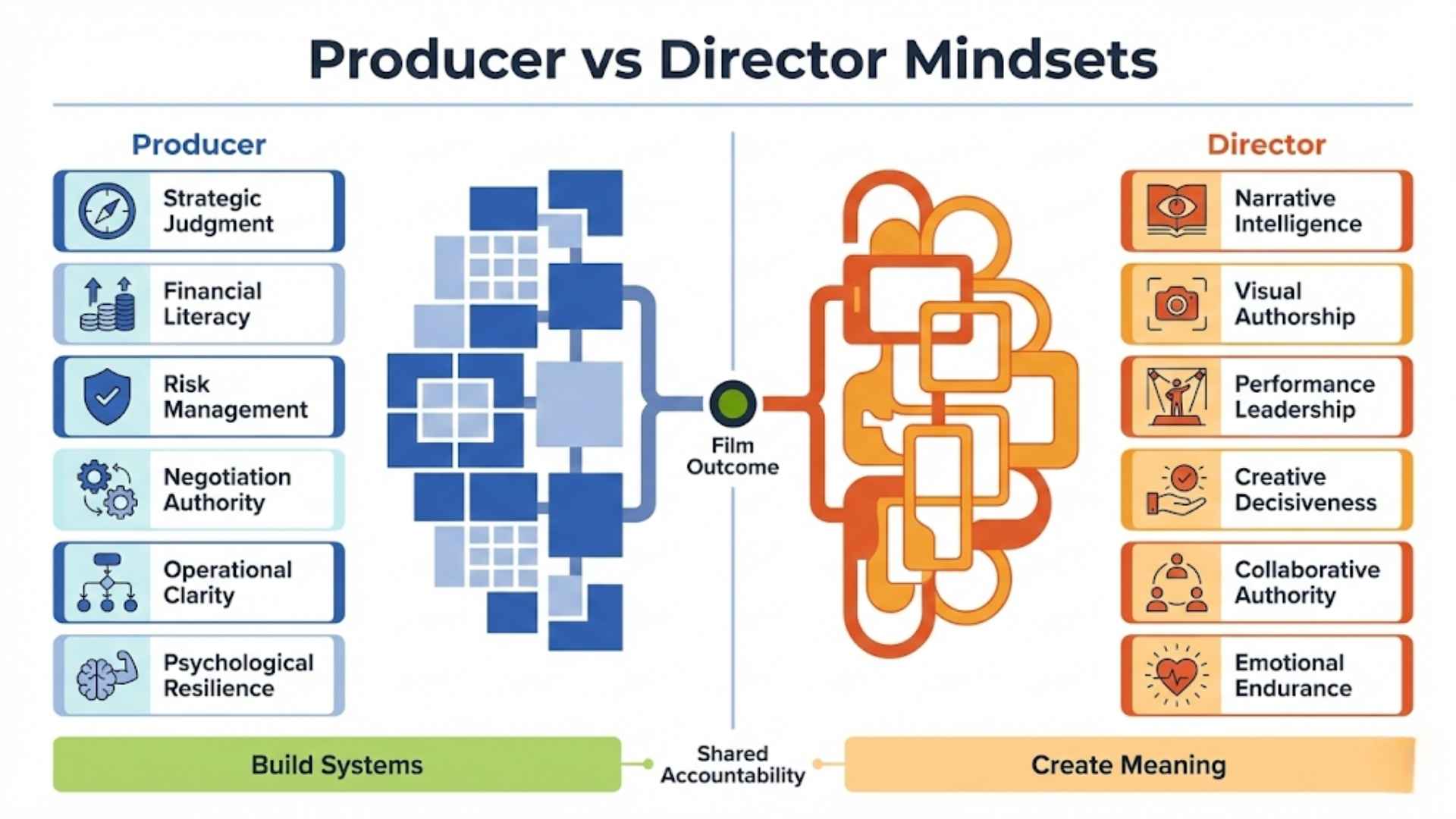

The difference between producer and director is not only functional. It is cognitive. These roles attract different types of thinkers, leaders, and decision-makers. When I evaluate talent for either position, I look less at résumé lines and more at how someone processes complexity, pressure, and accountability.

Skills and Traits of a Producer

Producing is not administration. It is authorship at the level of structure and risk.

I operate across creative, financial, legal, and operational systems simultaneously. Every decision affects cost, time, labor, and long-term viability. The core traits that define effective producers include:

Strategic judgment

I must evaluate whether a project is viable before years of work are committed. This includes assessing story, market, budget scale, financing likelihood, and distribution pathways.

Financial literacy

Budgets are not spreadsheets. They are narratives of risk. I need to understand what is truly flexible, where underestimation will break a schedule, and how cost decisions will affect post-production and delivery.

Risk management

Every project involves exposure. Legal, financial, reputational, and operational risks are always present. I constantly weigh whether a creative or logistical choice strengthens or destabilizes the project.

Negotiation and authority

I negotiate with financiers, agents, unions, distributors, and creatives. I must assert boundaries without eroding trust. If I cannot say no, I cannot protect the production.

Operational clarity

Complex productions collapse when communication fails. I am responsible for ensuring alignment across departments, timelines, and obligations. If a production drifts, that is my failure.

Psychological resilience

Producing requires absorbing pressure from every direction. When a project falters, I do not externalize responsibility. I own the outcome.

Good producers do not seek visible creative credit. We seek functional integrity. The film must survive development, production, delivery, and distribution.

Skills and Traits of a Director

Directing is not control. It is coherence.

A director must impose narrative and emotional order on an inherently chaotic process without suppressing spontaneity or discovery. The defining traits of strong directors include:

Narrative intelligence

A director must understand what the story is actually about beneath plot mechanics. Without that, visual choices become decorative rather than expressive.

Visual authorship

Directors think in images, rhythm, spatial relationships, and juxtaposition. Meaning emerges from framing, movement, pacing, and silence as much as from dialogue.

Performance leadership

Actors do not need commands. They need intention, context, and emotional alignment. A director must translate abstract story goals into human behavior.

Creative decisiveness

Production rarely allows for prolonged debate. The director must choose and commit. Indecision erodes momentum and confidence across the set.

Collaborative authority

Directing is orchestration. The strongest directors listen deeply to their department heads and integrate their expertise into a unified whole rather than imposing solutions in isolation.

Emotional endurance

Directors live inside the material for years. They carry the psychological weight of the story through development, production, post, and release. If they cannot tolerate vulnerability, doubt, and criticism, the work will fracture.

Where producers build systems, directors give those systems meaning.

Job Stability, Risk, and Industry Influence

Job Stability, Risk, and Industry Influence

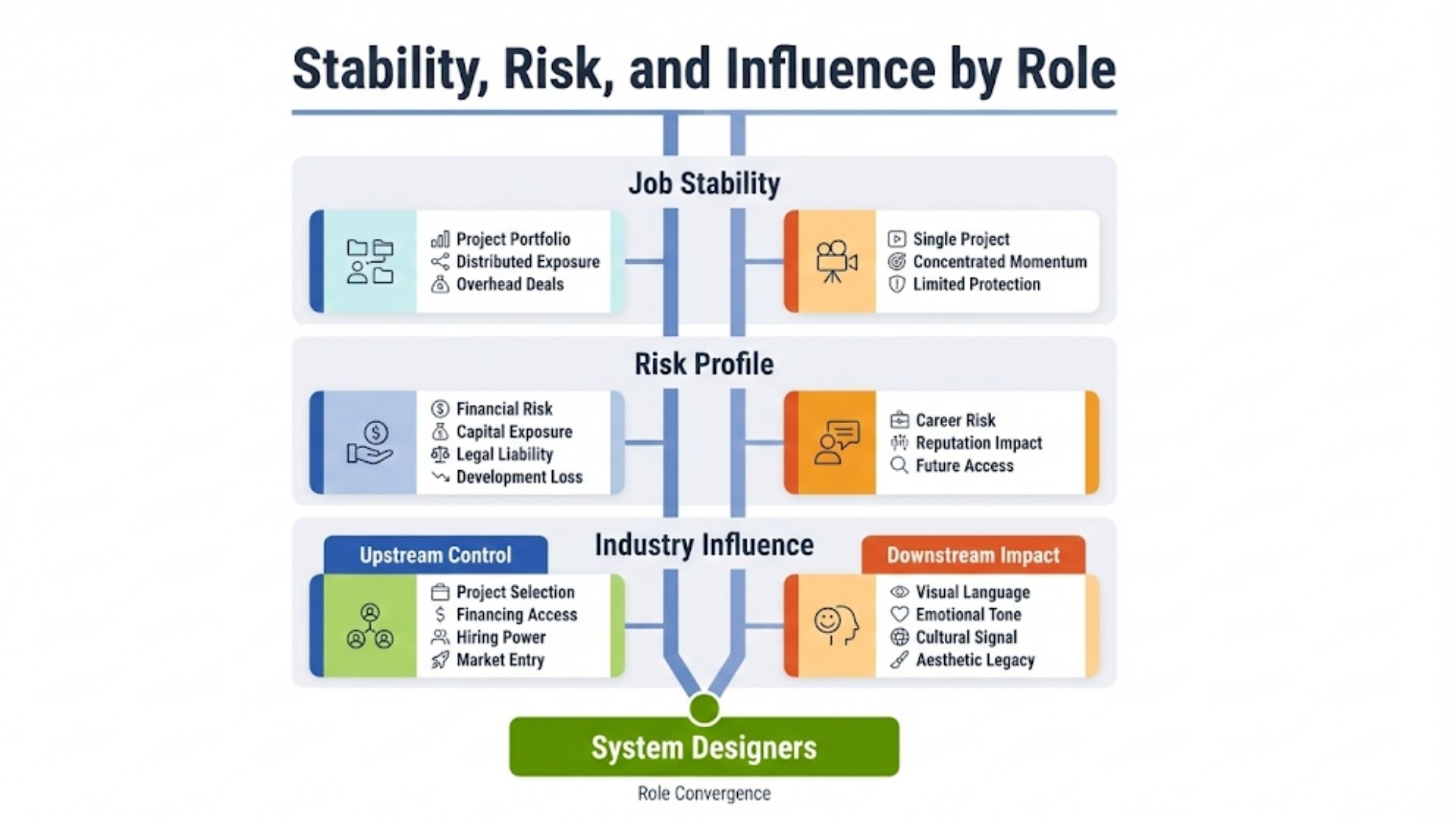

Job Stability

Neither role offers conventional stability. Filmmaking is project-based. Income is episodic. Employment is not guaranteed.

However, instability manifests differently.

As a producer, I can manage a portfolio of projects:

- Multiple titles in development.

- Several in financing.

- One or two in production or post.

If some collapse, others may advance. My exposure is distributed.

Directors usually concentrate on one project at a time. Their professional momentum often hinges on the reception of that single work. If it fails critically or commercially, there is no built-in diversification.

Producers who operate under studio or platform deals gain relative stability through overhead arrangements and multi-project commitments. Directors rarely receive equivalent structural protection.

Risk

The nature of risk differs by role.

For producers:

- I absorb financial risk.

- I invest time and often capital in projects that may never be produced.

- I carry legal, labor, and delivery exposure.

- If a project collapses in development, the loss is mine.

For directors:

- Financial risk is minimal once production begins.

- Career risk is substantial.

- A poorly received film can stall or derail future opportunities.

In practical terms:

- If a film fails before production, the producer loses resources.

- If a film fails after release, the director often loses momentum.

Both risks are severe. They simply operate on different axes.

Industry Influence

Producers shape what gets made.

We determine:

- Which projects enter development.

- Which scripts receive financing.

- Which directors are hired.

- Which stories reach the marketplace.

Our influence exists upstream of the creative process.

Directors shape how stories are told.

They define:

- Visual language.

- Emotional tone.

- Cultural impact.

- Aesthetic standards that influence future work across the industry.

Their influence is downstream, embedded in the art itself.

At the highest levels, influence converges. The most powerful filmmakers combine both roles. They control development, financing, and creative execution. They do not merely participate in the system. They design it.

Final Thoughts: Two Forms of Authorship

The persistent misunderstanding between producer and director comes from framing filmmaking as either art or business. In reality, it is a synthesis of both, executed under constant constraint.

As a producer, I create the conditions under which a film can exist. I manage risk, assemble resources, structure the production, and deliver a product to the marketplace. Without that framework, no amount of creative brilliance reaches an audience.

The director transforms that framework into meaning. They convert logistics into emotion, planning into narrative, and labor into experience. Without that vision, the structure remains empty.

We do not perform interchangeable functions. We practice different forms of authorship.

When the collaboration is disciplined and mutual, the film becomes more than the sum of its parts. When either role dominates without respect for the other, the work fragments.

This is not a hierarchy. It is interdependence.

A producer without a director builds nothing that endures.

A director without a producer creates nothing that survives.

That is the reality of professional filmmaking.

LocalEyes: Where Production Strategy Meets Directorial Craft

LocalEyes: Where Production Strategy Meets Directorial Craft

At LocalEyes, we operate in the exact space this article has explored: where the structure of producing and the vision of directing come together. We do not treat video as either a purely creative exercise or a purely operational task. Every project we take on is built with both in mind. We design the production framework that makes great storytelling possible, and we execute that story with Emmy Award–winning quality.

Our track record reflects that approach. With more than 3,900 videos created for over 300 clients, recognition on the Inc. 5000 list for three consecutive years, and more than 500 five-star reviews across Clutch, DesignRush, and Google, we have built our reputation by delivering work that performs in the real world. From our California headquarters and full-service offices in Atlanta, Austin, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, and San Diego, we provide national reach with true local expertise.

Whether we are producing testimonial, product, brand, corporate, explainer, educational, promotional, event, or animation content, our philosophy stays the same. We combine the strategic discipline of producing with the creative precision of directing so our clients receive more than a video. They receive a business tool designed to create a measurable impact.

If you are looking for a production partner that understands both the craft and the commercial reality of filmmaking, we would love to work with you. Contact LocalEyes today and let us build a video that is as strategically sound as it is creatively powerful.

Founder at LocalEyes Video Production | Inc. 5000 CEO | Emmy Award Winning Producer

Roles and Responsibilities on a Film Project

Roles and Responsibilities on a Film Project Differences in Creative Control and Decision-Making Authority

Differences in Creative Control and Decision-Making Authority

Day-to-Day Tasks Across Production Phases

Day-to-Day Tasks Across Production Phases

Salary Ranges and Compensation Structures

Salary Ranges and Compensation Structures High-Profile Examples of Successful Producers and Directors

High-Profile Examples of Successful Producers and Directors Influence on the Final Film and Public Recognition

Influence on the Final Film and Public Recognition Skills and Traits Required for Each Role

Skills and Traits Required for Each Role Job Stability, Risk, and Industry Influence

Job Stability, Risk, and Industry Influence LocalEyes: Where Production Strategy Meets Directorial Craft

LocalEyes: Where Production Strategy Meets Directorial Craft